Puerto Rico Coffee Industry

By the 1530s when its gold mines were exhausted, Puerto Rico was insignificant to the Spanish Crown as a source of wealth and trade when compared to the larger colonies of Santo Domingo and Cuba which had already turned into predominantly agricultural economies. For most of its history, sugar was the main agricultural product of the island with coffee, tobacco, ginger, indigo and cotton being minor crops. In Fray Iñigo Abad y Lassierra 1788 book Geographical, Civil and Natural History of the island of San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico he stated that:

"Agriculture is the first of the arts and the real wealth of a state, it is at its very beginnings in the island. For the most part it is limited to the cultivation of legumes and fruits for personal consumption, without offering to commerce any amount worthy of attention…they dedicate great care to coffee, which bears fruit slowly, requires little care and has assured markets abroad where it is craved because of its quality and the harvest in a normal year like 1775 is 45,049 bushels."

The coffee plant is said to be native to the African Ethiopian region of Kaffa, it was in Europe that it first became a popular drink. The most accepted theory regarding the arrival of the coffee plant in Puerto Rico is that it was brought by the Spaniards in 1736. According to Historian Fernando Picó, in the 1780s coffee became the principal agricultural export surpassing tobacco. By 1812 activities related to the export of sugar and coffee were the principal activities dominating the island's economy. Archeologist Luis Pumarada states that sugar for export disappeared in the 1700s when the local industry turned to the production of molasses. Around 1770, coffee became the main agricultural export product until ca. 1830 when sugar again took over as the main export product for a short twenty years when coffee again became the main export product until ca. 1902.

The first census available in Puerto Rico was made by Alejandro O'Reilly in 1765 which stated the island's population at 44,883 inhabitants. As a result of the Spanish Crown's Royal Decree of 1778 that allowed trade with other colonies and most ports in Spain and the Royal Decree of 1779 that allowed slave trade, the population of the sparsely populated island grew almost fivefold from 44,883 to 220,892 in the fifty years between 1765 and 1815 according to population numbers reported by Fray Iñigo Abad.

The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 that granted naturalization to foreigners that worked the land given them and pledged allegiance to the Catholic Church and the Spanish Crown, created a further increase in population and in agricultural activity in Puerto Rico. In the seventeen years after the Royal Decree of Graces, the island's population grew at an annual rate of 4.4% from 220,892 in 1815 to 350,051 in 1832. The first census after the 1898 US occupation taken as of November 10, 1899 reported a population increase of 613% to 953,243 from 155,426 in 1800.

Due to the Haitian Revolution, the coffee industry in Puerto Rico was greatly improved with the immigration of French citizens from Haiti which at the time was the major exporter of coffee to world markets. After 1815 there was an influx of people from the Mediterranean Island of Corsica who settled around the municipalities of Yauco and Maricao and dedicated themselves to cultivating coffee, Corsicans and Yauco are to this day widely associated with coffee production in Puerto Rico. According to Archeologist Luis Pumarada, in 1829 Mayagüez was the major port for export of coffee in Puerto Rico since the majority of the French immigrants settled in the western part of the island. Corsicans contribution to the development of the coffee industry in Puerto Rico was undoubtedly very important, but the unheralded contribution of Catalonians and Majorcans who owned the majority of haciendas in Maricao and Lares had as much if not more influence.

Even though by the 1830s sugar exports began to surpass those of coffee, in the latter part of the 19th Century due to an increase in world coffee prices and a crisis in the sugar industry, coffee production began to surpass sugar and it was during this time that coffee exports to Europe started to grow and Puerto Rican coffee obtained one of the highest quotations in world markets. By 1935 though, the trend had shifted dramatically with sugar accounting for 60%, coffee 3% and tobacco 9%.

By 1877 there were eight hundred forty three registered coffee haciendas throughout approximately sixty nine municipalities, two hundred thirty four of them in Maricao. During the second half of the 19th Century, Puerto Rico enjoyed a second-to-none prestige in the coffee world. By the 1890s Puerto Rico was the sixth largest exporter of high grade coffee worldwide and the fourth largest in the Americas. According to the 1899 Census Records, land dedicated to growing coffee in 1897 was one hundred twenty two thousand three hundred fifty eight cuerdas while only sixty one thousand five hundred fifty six were used to grow sugarcane. Coffee production peaked in 1898 when exports were approximately 600,000 quintals.

Unfortunately, after the Spanish-American War of 1898, the island's coffee industry started to slowly fade due to Hurricane San Ciriaco of 1899 that destroyed the coffee crop, to the fact that the newly arrived US investors were more interested in the sugar industry and to the fact that Spain, until then its major market could no longer import Puerto Rican coffee tariff free as a colonial product. The Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer in its February 8, 1908 edition states:

"The natives cannot understand why the United States does not place a heavier tax on the coffee that comes from Brazil and other South American countries, thereby giving the Porto Rican product protection. They do not realize that the whole output of coffee in Porto Rico would hardly more than supply New York City. Under Spanish rule Porto Rico sold nearly all of its coffee to Spain, but when the island became part of the United States, the Spanish Government, of course, placed a tariff on Porto Rican products, as did Cuba. The result was the market for Porto Rican coffee was largely taken away. Recently the reduction of the maximum French tariff on Porto Rican coffee has opened up a market for that product, and the coffee planters are happy."

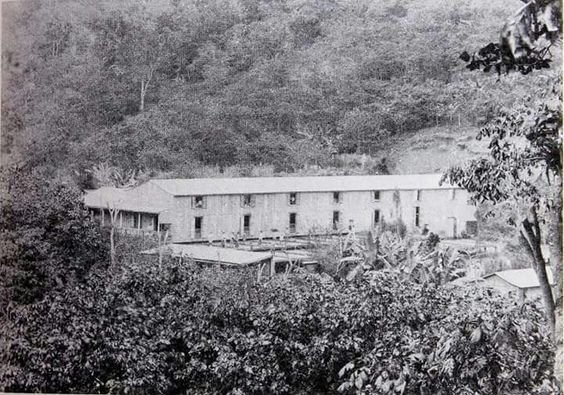

By 1969 Puerto Rican coffee had practically disappeared from the world markets. Today the coffee zone on the island includes twenty two municipalities and export production is approximately 12,500 quintals or 2% of the exports in 1898. Of the haciendas that operated during the late 1800s, there are still a few that remain, some still in operation which location can be identified in the Maps page. In the coffee haciendas pages, I will try to document in pictures thirty seven haciendas that operated in the 1800s and early 1900s and their current state.

A big thank you goes to Dr. Lillian M. Lara Fonseca at the State Historic Preservation Office who allowed us to review valuable documents and reproduce pictures used to document information herein provided. Another big thank you goes to Archeologist Dr. Luis Pumarada O'Neill and Lisette Fas Quiñones of Cafiesencia Puerto Rico for contributing to this project by sharing their work and extensive knowledge in the history of the Puerto Rican Coffee industry.

The gallery below includes a few vintage photos of haciendas that existed during the 19th Century and early 20th Century for which today there are no remains.

Value of Exports (%)

Coffee Exports

Coffee Production

Land Dedicated to Coffee

Hacienda Limani - Adjuntas

Hacienda Santa Engracia - Maricao

Hacienda Esperanza - Adjuntas

Hacienda La Merced - Guayanilla